Coloring horror

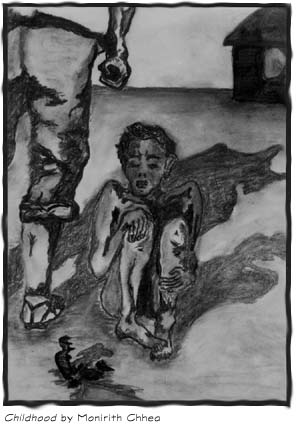

The entire time I knew him, Pao Vu did only one thing. He colored. Pao Vu was from Cambodia. He was eight years old when I met him in Mrs. Cover's third grade class. I was a senior in high school and a teacher's aide. I showed up for about an hour every other day. Pao Vu showed up about mid-semester. I was supposed to help him learn English. Third-grade days at East Elementary typically involved Elmer's glue, construction paper, flashcards, math equations and a reading group hierarchy defined by red, blue and brown. I would sit with Pao Vu, trying to explain whatever was going on. I'd point to the words as Mrs. Cover read from a third-grade textbook. I traced letters on big-lined notebook paper. I dutifully sprinkled glitter on strands of glue that spelled our names. Mostly, I'd watch him press crayon after crayon into sheet after sheet of notebook paper, thinking I'd met an eight-year-old who already knew far more than I ever would. It was 1979. In the years before Pao Vu was born, the war in Vietnam spilled over into the land of his Buddhist ancestors. By the second year of his life, nearly 540,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on Cambodia, a nation about the size of Missouri. When Pao Vu turned four, a mad man ruled his country. Within moments of coming to power, this man evacuated every major city. He made farmers of bankers and store clerks. He made corpses of professors and doctors. It is said that Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge killed nearly one-fifth of the Cambodian population. America could not be bothered to intervene. We had just been humiliated in Southeast Asia. We learned "The Hustle" while this butcher had his way. Whatever Pao Vu saw during the eight years of his life, I could only imagine from the images that issued forth from his crayons. While other kids worked out stick figures and smiley-faced sunshines, Pao Vu articulated great battle scenes. Zooming fighter planes and looming bombers strafed a rolling, forested countryside. Orange and red flames leapt up from the land. Miniature people fled in horror. Always, in the center of the chaos, a lone figure - a massive powerful warrior, knocking planes out of the sky with one of many gigantic swords he held in each hand. This, I presumed, was Pao Vu. The tiny warrior was never impolite to me. He never pushed away the books or the flashcards. He occasionally looked me in the eye when I spoke, but he would have nothing to do with learning the alphabet, making paper-bag puppets or memorizing multiplication tables. What meaning could any of this have for a child born beneath bombs and raised among boneyards? What relevance could third-grade social studies have to a child who escaped decimation by crossing the Pacific Ocean in a rickety, wooden boat? How in God's name was glitter and glue going to acclimate a child from a Buddhist, mountain culture to the middle of Nebraska? I didn't know what Pao Vu needed back then. I suppose few people did. Few Americans had been driven from their homes with nothing but the clothes on their back and put to work as slave labor. No one I knew in Cozad ever saw their family members gunned down or beaten to death. None of us had ever suddenly found ourselves making a new home thousands of miles away, among people who didn't even look like us. I did understand one thing Pao Vu needed to master of all his nightmares. Pao Vu needed to color. Monday, April 12, 1999

Copyright 2010 by Deborah McAdams. All Rights Reserved. For Reprint Rights, click here.

|